Implementation of Diversion Programme: Ideal vs. Real

There is a critical disconnect between the intended purpose of the Juvenile Justice Act (JJ Act) and its actual implementation. The JJ Act recognizes the need for a tiered approach to handling juvenile cases (case gradation). This approach aims to reduce the burden on the JJB system by prioritizing cases requiring formal intervention; Provide more suitable services tailored to the specific needs of each child. Despite the JJ Act’s provisions, case gradation isn’t a prominent feature in JJB operations. The relevant provisions in the JJ Act don’t explicitly link case gradation to diverting children away from the formal system. While the Model Rules introduced a provision for police to only apprehend children for serious offences, has this been implemented in reality is to be seen? The lack of a clear and functional case gradation system can lead to JJB’s resources being stretched thin due to an influx of cases that could potentially be handled differently. Children involved in minor offences potentially going through the entire formal JJB process, which might not be the most appropriate response. Imagine two children:

- Child A is caught shoplifting for the first time.

- Child B is caught with a weapon and involved in a violent crime.

In a well-functioning case gradation system, Child A might be offered diversion programs or alternative solutions outside the formal JJB process. Child B, due to the seriousness of the offense, would likely go through the full JJB process.

A crucial missing element in India’s juvenile justice system: a lack of clear guidelines for diversion. This lack of a formal system for diversion could be due to two reasons First, policy rejection by the stakeholders involved, but it is less likely. Second, and more likely is the lack of guidance on how and when to divert cases from formal proceedings, which is hindering its implementation.

Thus, by explicitly establishing diversion as a core principle of the juvenile justice system, India can encourage its use in everyday practices. This aligns with the overall goals of the JJ Act and benefits both children and the JJB system. Because diversion can help children avoid unnecessary exposure to the formal justice system, especially for serious and petty offences. Similarly, diversion can free up JJB resources for cases that truly require formal intervention. Given the reluctance to grant bail during investigations, diversion offers a way to provide children with services or sanctions without exposing them to the harms of secure detention.

Building a Structured Diversion Program:

- The first step is to explicitly define diversion and its goals within the JJ Act and Model Rules. This provides a clear legal framework for its use.

- Developing a successful diversion program requires agreement on its purpose and process among all actors involved, especially the police (the usual first point of contact). Open discussions are crucial to achieve this consensus.

- While reducing JJB caseloads is a benefit, diversion shouldn’t be solely focused on this. Its true value lies in providing effective non-judicial alternatives for sanctions and rehabilitation. Successful diversion programs offer intensive and comprehensive services. Simply reducing the number of cases won’t be enough unless the alternatives offered are effective.

- Therefore, before implementing diversion, a realistic assessment of available resources is essential. Some alternatives like community service can be readily implemented, while others like drug treatment might require additional investment. The diversion program should be tailored to the services that can be effectively delivered with available resources. Effective diversion requires monitoring compliance with diversion agreements. Probation officers, courts, or designated personnel should be responsible for this task.

- By addressing these concerns, diversion can become a valuable tool for the JJB system. It allows them to focus limited resources on children who need them most and it effectively address minor offenses in a less resource-intensive way.

- Program design should consider the child’s – Age, Maturity level, Religious and cultural background, Specific needs and circumstances. The program should also address the needs of any victims involved. But diversion is not a one-size-fits-all solution. While diversion offers numerous benefits, it’s not mandatory for every case.

- The decision to use diversion should be based on what’s best for the child’s individual circumstances. Considering factors like the severity of the offence, the child’s history, and their willingness to take responsibility can help determine the most appropriate course of action.

To illustrate the above, imagine two children caught shoplifting for the first time. Child A readily admits their mistake and expresses remorse. Child B denies any wrongdoing. Child A might be a good candidate for diversion, while Child B might benefit more from the structure and accountability offered by the formal court system. This tailored approach ensures that each child receives the intervention they need to make positive changes.

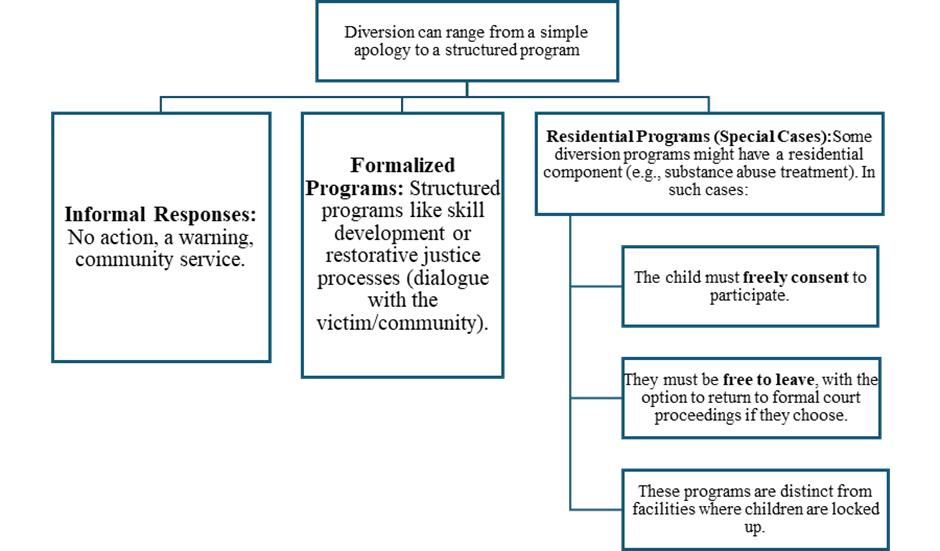

Diversion can range from a simple apology to a structured program. Here are some examples:

Diversion programs should be designed based on factors like the offence’s severity and the child’s individual needs. Clear guidelines are crucial, specifying – Who has the authority to determine program duration and intensity. And procedures for resuming formal proceedings if the child violates diversion agreement terms.

While preparing a diversion programme, one thing has to be kept in mind that diversion isn’t synonymous with restorative justice or child rights-based interventions. This means diversion programs must adhere to specific ground rules of upholding child rights principles and restorative justice principles.

Imagine two children caught vandalizing a public property for the first time. Child A might receive a simple warning from the police and community service as part of a diversion program (informal and formal responses). Child B, if the offense was more serious and they had a history of vandalism, might participate in a longer program focused on anger management and counselling (tailored program and restorative justice elements). By offering a flexible range of options and ensuring adherence to child rights principles, diversion programs can become valuable tools for promoting rehabilitation and positive change within the juvenile justice system. Thus, diversion programs must not involve practices violating the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), such as: Corporal punishment, Public humiliation and Deprivation of liberty (including in “rehabilitation centres” or “special schools”).

Conclusion

The Juvenile Justice system in India has “Best interest of the child” at its centre. One of its major aims is crime prevention but the child’s reasons for indulging in them need to be given equal weightage. The Act aims to do that through the formation of the Juvenile Justice Board. This Board has to include professionals such as social workers and psychologists to understand the nuances. Their combined expertise allows for interventions tailored to each child’s specific needs. Excluding any child from the JJ system’s protection undermines the principle of diversion.

The concept of “diversion” extends beyond simply releasing children from Child Care Institutions (CCIs). It can also involve reintegrating them into family or community settings through bail and final orders. The JJ Act (2000 & 2015) further emphasizes this with its dedicated chapter on Rehabilitation & Social Reintegration. The Police alone cannot decide on diversion from the JJ system. The JJB, after hearing all parties involved, determines the appropriate level of intervention based on the child’s needs and the specifics of the case.

Ideally, decisions should be based on the “circumstances of the child.” Unfortunately, the current practice often prioritizes the “nature of the offence” alone in determining intervention.

The Model Rules offer some guidelines for handling minor offences without formal court proceedings, but these are scattered and lack a clear policy statement promoting diversion. Police often resort to formal procedures even for minor offences, putting a strain on the JJB system. There seems to be a lack of awareness among police and JJB members about existing provisions for handling minor offences informally.

Diversion can free up JJB resources for cases that truly require formal intervention. Children with minor offenses can receive targeted services outside the formal system. Avoiding formal charges can lessen the negative impact on children. Diversion programs can be more cost-effective than formal court proceedings.

The JJ Act and Model Rules don’t explicitly prioritize diversion as a key strategy. There’s no clear system for identifying cases suitable for diversion. Police and JJB members may not be fully aware of or trained on diversion practices.

Thus, the JJ Act and Model Rules should explicitly define diversion and its goals. All stakeholders, especially police as the first point of contact, need to be involved in designing and implementing diversion programs. Diversion must offer effective alternatives like community service or rehabilitation programs. A system needs to be set up to ensure compliance with diversion plans. Available resources for alternative programs like counseling or drug abuse treatments must be realistically assessed. Diversion can be a valuable tool in India’s Juvenile Justice System. By addressing the issues mentioned above and learning from successful models like the US, India can implement diversion programs that benefit both children and the JJB system as a whole.

(I express my sincere gratitude to Mr. Vishwadeep Chandrakar and Ms. Mansi Chauhan for their assistance in compiling this work. Given my limited expertise in this area, I am committed to a nuanced exploration of the topic. Feedback is therefore warmly welcomed.)

Reference – 1 (The Beijing Rules)

The Beijing Rules states that “11.1 Consideration shall be given, wherever appropriate, to dealing with juvenile offenders without resorting to formal trial by the competent authority, referred to in rule 14.1 below.

11.2 The police, the prosecution or other agencies dealing with juvenile cases shall be empowered to dispose of such cases, at their discretion, without recourse to formal hearings, in accordance with the criteria laid down for that purpose in the respective legal system and also in accordance with the principles contained in these Rules.

11.3 Any diversion involving referral to appropriate community or other services shall require the consent of the juvenile, or her or his parents or guardian, provided that such decision to refer a case shall be subject to review by a competent authority, upon application.

11.4 In order to facilitate the discretionary disposition of juvenile cases, efforts shall be made to provide for community programmes, such as temporary supervision and guidance, restitution, and compensation of victims.

Commentary

Diversion, involving removal from criminal justice processing and, frequently, redirection to community support services, is commonly practised on a formal and informal basis in many legal systems. This practice serves to hinder the negative effects of subsequent proceedings in juvenile justice administration (for example the stigma of conviction and sentence). In many cases, non-intervention would be the best response. Thus, diversion at the outset and without referral to alternative (social) services may be the optimal response. This is especially the case where the offence is of a non-serious nature and where the family, the school or other informal social control institutions have already reacted, or are likely to react, in an appropriate and constructive manner.

As stated in rule 11.2, diversion may be used at any point of decision-making-by the police, the prosecution or other agencies such as the courts, tribunals, boards or councils. It may be exercised by one authority or several or all authorities, according to the rules and policies of the respective systems and in line with the present Rules. It need not necessarily be limited to petty cases, thus rendering diversion an important instrument.

Rule 11.3 stresses the important requirement of securing the consent of the young offender (or the parent or guardian) to the recommended diversionary measure(s). (Diversion to community service without such consent would contradict the Abolition of Forced Labour Convention.) However, this consent should not be left unchallengeable, since it might sometimes be given out of sheer desperation on the part of the juvenile. The rule underlines that care should be taken to minimize the potential for coercion and intimidation at all levels in the diversion process. Juveniles should not feel pressured (for example in order to avoid court appearance) or be pressured into consenting to diversion programmes. Thus, it is advocated that provision should be made for an objective appraisal of the appropriateness of dispositions involving young offenders by a “competent authority upon application”. (The “competent authority,” may be different from that referred to in rule 14.)

Rule 11.4 recommends the provision of viable alternatives to juvenile justice processing in the form of community-based diversion. Programmes that involve settlement by victim restitution and those that seek to avoid future conflict with the law through temporary supervision and guidance is especially commended. The merits of individual cases would make diversion appropriate, even when more serious offences have been committed (for example first offence, the act having been committed under peer pressure, etc.).”

Reference -2 (The Tokyo Rules)

“3.1 The introduction, definition and application of non-custodial measures shall be prescribed by law.

3.2 The selection of a non-custodial measure shall be based on an assessment of established criteria in respect of both the nature and gravity of the offence and the personality, background of the offender, the purposes of sentencing and the rights of victims.

3.3 Discretion by the judicial or other competent independent authority shall be exercised at all stages of the proceedings by ensuring full accountability and only in accordance with the rule of law.

3.4 Non-custodial measures imposing an obligation on the offender, applied before or instead of formal proceedings or trial , shall require the offender’s consent.

3.5 Decisions on the imposition of non-custodial measures shall be subject to review by a judicial or other competent independent authority, upon application by the offender.

3.6 The offender shall be entitled to make a request or complaint to a judicial or other competent independent authority on matters affecting his or her individual rights in the implementation of noncustodial measures.

3.7 Appropriate machinery shall be provided for the recourse and, if possible, redress of any grievance related to non-compliance with internationally recognized human rights.

3.8 Non-custodial measures shall not involve medical or psychological experimentation on, or undue risk of physical or mental injury to, the offender.

3.9 The dignity of the offender subject to non-custodial measures shall be protected at all times.

3.10 In the implementation of non-custodial measures, the offender’s rights shall not be restricted further than was authorized by the competent authority that rendered the original decision.

3.11 In the application of non-custodial measures, the offender’s right to privacy shall be respected, as shall be the right to privacy of the offender’s family.

3.12 The offender’s personal records shall be kept strictly confidential and closed to third parties. Access to such records shall be limited to persons directly concerned with the disposition of the offender’s case or to other duly authorized persons.“

Reference – 3

Ericka Rickard and Jason M Szanyi, Bringing Justice to India’s Children: Three Reforms to Bridge Practices with Promises in India’s Juvenile Justice System

Reference – 4

STUDY MATERIAL FOR JUVENILE JUSTICE (CARE AND PROTECTION OF CHILDREN) ACT, 2015 SEPTEMBER 2022 (TN State Judicial Academy)