Overview

The principle of diversion seeks to establish alternate measures for children in conflict with the law, with a view of resorting to court proceedings as a last resort. This approach prioritises the well-being of children and society as a whole (Juvenile Justice Act, 2015, Section 3(xv)).

The Committee on the Rights of the Child’s General Comment No. 24 (2019)[i] has stated that diversion should be “an integral part of the child justice system” and “the preferred manner of dealing with children in conflict with the law in the majority of cases”. The Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989)[ii] prioritizes diversion. It states that “State Parties shall seek to promote, whenever appropriate and desirable, measures for dealing with children in conflict with the law without resorting to judicial proceedings providing that human rights and legal safeguards are fully respected.”[iii] One of the eight general principles is the “primacy of alternative measures to judicial proceedings [diversionary measures]”[iv]. When considering diversion, the competent authority takes into account the seriousness of the offence, the age of the child, the circumstances of the case, and any previous offending behaviour.

The United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Administration of Juvenile Justice (“The Beijing Rules”) (1985)[v] puts emphasis on the alternatives to formal trial of the juvenile offenders. It also says that certain institutions shall be given powers to dispose of such cases. Under the Beijing Rules, consent of the juvenile or their family members must also be sought to facilitate diversion.

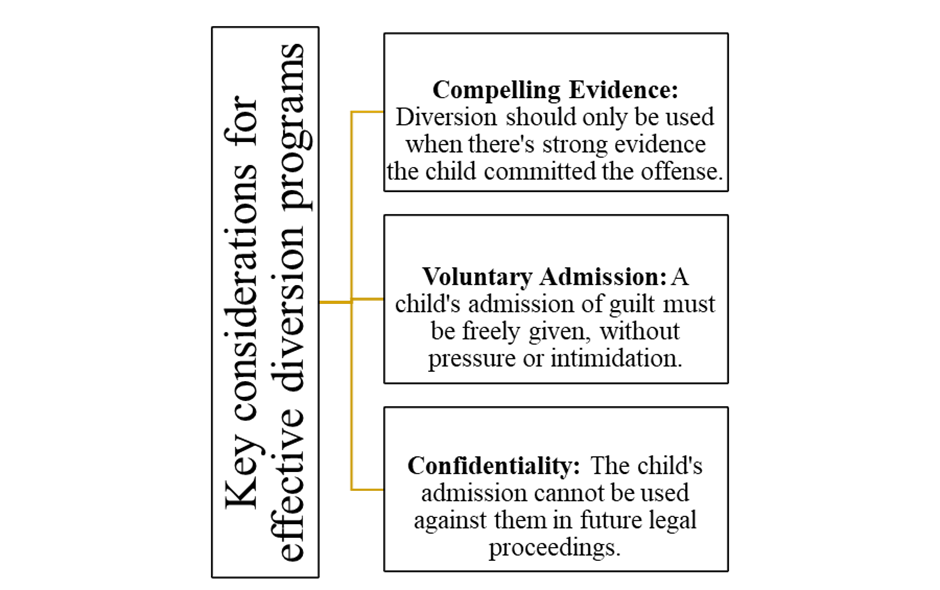

The Tokyo Rules (1990)[vi] simplified certain provisions of the Beijing Rules and focused on legally prescribed non-custodial measures. According to it, both quantitative and qualitative measures regarding the nature and offence of crime as well as the personality and background of the offender shall be used for selection of non-custodial measures. Individual rights, dignity, and consent of the child need to be given considerable weightage. Additionally, UN General Comment No. 10[vii] emphasizes that diversion should be a well-established practice, especially for minor offences. It highlights the benefits of diversion. It clarifies that diversion is not limited to minor offences.[viii] It can be effective for a wider range of situations. Key considerations for an effective diversion programs as per the Tokyo Rules are as under[ix]:

India’s support for diversion reflects a broader global commitment. The Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), ratified by India in 1992, focuses on establishing separate procedures for children in conflict with the law.[x] This paves the way for diversion programs.

Diversion can offer several advantages including but not limited to First, Reduced Stigma: Child is able to avoid the negative label associated with the criminal justice system; Second, Rehabilitation Focus: Diversion programs can address the root causes of offending behaviour, promoting positive change; Third, Public Safety: By helping children develop better-coping mechanisms, diversion can contribute to a safer society; Fourth, Cost-Effectiveness: Diversion programs can be less expensive than formal court proceedings.

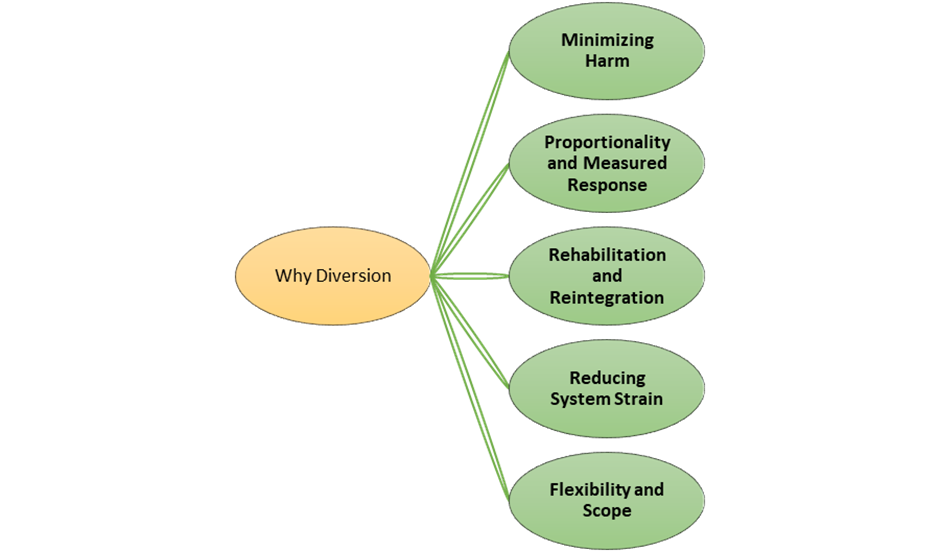

Why Diversion Matters in Juvenile Justice

There are several key reasons why diversion is a crucial element in juvenile justice systems. Diversion seeks to shield children from the potentially negative consequences of formal court proceedings. These consequences could include emotional distress, stigma, and a lasting criminal record. It embodies the principle of proportionality, ensuring the response to an offense is appropriate to its severity. It avoids ‘over-reacting with the full weight of the justice system’ for minor offenses. Diversion prioritizes the child’s rehabilitation and reintegration back into society. By focusing on alternative solutions it provides opportunities for the child to address the root causes of offending behaviour and become a productive member of society. It can help alleviate the strain on the juvenile justice system by lowering the number of children detained in police custody and pre-trial facilities and decreasing the number of cases clogging the courts. In theory, diversion can be applied to a wide range of offences, though it’s typically not used for henious crimes or repeat offenders. This flexibility allows for a tailored approach based on the individual circumstances of each case.

To illustrate the concept, imagine a child caught shoplifting for the first time. Diversion might involve community service, mediation with the store owner, or counselling to address why the child committed the offence. This approach allows the child to learn from their mistake without the potential harmful effects of the formal court system.

The concept of diversion in India still lacks clear understanding due to which the policy of diversion is not standardised and not applicable uniformly. The next part of this work will focus on the provisions in the JJ Act and Rules that have the essence of diversion.

[i] https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/general-comments-and-recommendations/general-comment-no-24-2019-childrens-rights-child – (paragraph 16)

[ii] https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/ProfessionalInterest/crc.pdf

[iii] (article 40(3)(b))

[iv] (article 13(4))

[v] United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Administration of Juvenile Justice (“The Beijing Rules”)

[vi] United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for Non-custodial Measures (“The Tokyo Rules”)

[vii] Para 24.

[viii] Para 25.

[ix] Para 27.

[x] https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/crc.pd